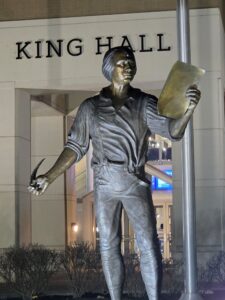

I believe that James Madison would have approved the Supreme Court’s recent overturn of the Trump tariffs. I’m writing this blog on the campus of James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, named for the chief architect of the U.S. Constitution. The outstanding JMU Rose Library is one of my favorite places to work.

James Madison (1751-1836) developed the concept of checks and balances in the federal government. He envisaged three branches, each of which could check the wrongful constitutional impulses of the others.

The Virginian understood human nature and its tendencies toward self-aggrandizement. “If men were angels,” Madison wrote in The Federalist #51, “no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, no government would be necessary.” Perhaps the most politically minded of the nation’s founders, Madison wrote that the federal government must be able to control the governed. Further, he emphasized, the national government is obliged to control itself.

I think that James Madison would have applauded the Supreme Court’s nine-member ruling on February 20, 2026. But to guess how he would have argued and voted had he served on the Court would be mere speculation. The six-member majority ruled that Trump lacked the legal authority to impose his tariffs. The power to tax, the Supreme Court asserted, was Congress’s responsibility, as outlined in Article 1, section 8: “The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises.”

It has been eight or nine generations since the U.S. founders wrote the Constitution. On our nation’s 250th birthday, it is not too much to be concerned about the effectiveness of Madison’s checks and balances among the Judicial, Executive, and Congressional branches. For example, the President has declared that he will seek other legal means to collect the import tariffs, thereby circumventing the Court’s ruling. But regardless of the outcome of the Supreme Court’s ruling, the very fact that a presidential action can be stricken, in such divided times as we live in, is remarkable.

There were those in the Constitutional era who wanted state governments to have greater power than the national government. Madison countered that only a strong central government could effectively rule a large republic. Further, he sought a way to keep the national government from becoming too powerful or domineering. Thus, as he read history, especially Montesquieu, he believed that a system of checks and balances at the national level was essential.

While at times it seems to many of us that the U.S. federal government is in perpetual gridlock, what we are actually observing is the sometimes-volatile interplay among three powerful branches of government, each with constitutional authority over the others. President Trump has been impeached twice by the House of Representatives, and each time the Senate acquitted him.

In the flow of national politics today, the Congress, divided and self-absorbed, seems unable to use the power granted it in the Constitution. When the Supreme Court, however, asserted its constitutional power and ruled 6-3 against the President’s tariff policies, it seems to me that James Madison would have applauded the nerve of those who voted against one of the most powerful chief executives in U.S. history.