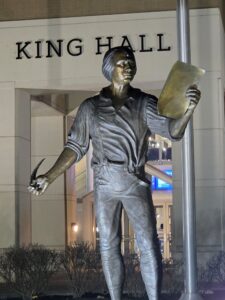

A lecture about 18th-century Mennonites, researched, written, and delivered by Elwood Yoder on February 13, 2025, Harrisonburg, Va. The lecture is on YouTube and includes accompanying PowerPoint slides.

Introduction

During the 1700s, Mennonite farmers sought land to own, cultivate, and pass on to their children, while they also sought renewal of faith for themselves and their communities. They hoped to be tolerated for their distinctive and radical beliefs, and many migrated to new places that offered them religious freedom.

Mennonites seemed to love the land. On the third day of creation, God created dry land called Earth, bringing forth all kinds of plants, crops, and trees. They liked Psalm 24:1, “The earth is the LORD’s and everything in it, the world and all who live in it” (NIV).

In this lecture, we will review the migration of Mennonites from the Netherlands east to Poland, Prussia, and Russia in search of land and religious toleration. Second, we will analyze why Mennonites fled Switzerland to the French Alsace and German Palatinate. Third, we will trace the westward migration of European Amish and Mennonite families who sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to a new world in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Ontario.

Dutch migration to Poland, Prussia, and Russia

A new homeland for Dutch Mennonites emerged when hundreds migrated east to Poland and Prussia. As early as the 1540s, persecution pushed Mennonites out of the Netherlands. Emperor Charles V unleashed furious persecution against Flemish Mennonites in Flanders in the 1530s and 1540s. They had to move. Many of those put to death in the Martyrs Mirror come from these difficult years of persecution. The violent disaster at Münster had tarred the reputation of Mennonites in the Netherlands. While some Dutch Mennonites grew wealthy, not all did so. Difficulties in making a living, wars, and rapid urbanization pushed many Dutch Mennonites to move east.

At the same time, nobles and ruling officials in the Polish province of West Prussia welcomed religious minorities. Rural Dutch Mennonite farm families felt pulled to the Vistula Delta of Polish Prussia. In Poland, they found religious tolerance offered by noblemen who wanted good farmers to raise grain, milk cows, and recover marginal land in the river delta. The nobility needed more farmers, so Mennonites from the Netherlands and North Germany moved east to seek better opportunities for themselves and their children.

The Vistula River in Poland seemed to call out for the Mennonites to move. In the 1540s, among the earliest to migrate, a dozen Flemish Mennonite families from Flanders fled persecution. They moved to Przechowko (pronounced Chee-hōf-ka) along the Vistula River, about sixty-five miles south of Danzig (modern Gdansk), along the Baltic Sea. By 1661, the Old Flemish Mennonites had established a thriving church in Poland, and other farm families from the Netherlands joined them. A trickle of migration turned into a steady stream of Mennonites who fled the Netherlands and northern Germany, such that by 1780, there were approximately 13,000 Mennonites in West Prussia.1 In the Netherlands, however, during the 1700s, the Mennonite population decreased by 83%, and 100 Dutch Mennonite congregations disappeared.2

Members of the Przechowko Mennonite Church built beautiful farms, planted orchards, dug roads and water canals, and operated Holland-style windmills that beautified the countryside.3 They supplemented their income with linen weaving. From the Old Flemish Church, the men wore long, drab, collarless coats with hooks and eyes instead of buttons. Marriage with outsiders was not tolerated, not even with the more progressive Frisian Dutch Mennonites.4 By the mid-1700s, they began to lose their Dutch language and started speaking West Prussian Plautdietsch, a low German dialect infused with Dutch words.

The agricultural skills of Dutch Mennonite immigrants enabled them to prosper in the Vistula Delta.5 Mennonites developed new solutions for crop farming and cattle breeding. They produced a unique yellow cheese that stayed fresh for a long time and could be shipped through the Baltic Sea to Amsterdam, London, and Lisbon.6 In the Vistula Delta, most of their villages and fields were below sea level, so they became experts at drying fields, managing drainage systems, and building raised dikes to keep the river water from flooding their farms.

Mennonites in Polish West Prussia leased blocks of land from Polish noble barons, sometimes as many as 2,500 acres in a section. Polish Mennonite farmers installed a windmill at the lowest place on their farm to pump water away from their fields, which might take three to four generations to implement.7

By the late 1700s, Mennonites in Prussia made up the largest group of Mennonites in the world. They had numerous settlements in the Vistula River region. A few lived in the bigger cities and worked in the trades, especially in the 1600s, though guilds did not want the Mennonites working in their industries, so Mennonites farmed. Some of the names in Przechowko Mennonite Church in Prussia included Klassen, Thiessen, Janzen, Duerksen, Voth, Unruh, Schmidt, Sawatzky, and Ratzlaff.

By the end of the 1700s, Poland disappeared from the map, swallowed up in war by Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Poland reappeared on the European map after World War I, 125 years later. When the Prussian Kings took away their religious freedoms, especially the military exemption for Mennonite men, tens of thousands of Vistula Delta Mennonites migrated to South Russia along the Dnieper River.

Approximately 40-50 families from Przechowko Mennonite Church migrated to Russia. When a group traveled to Russia in 1821, they met Tsar Alexander I. Tsar Alexander got out of his carriage and asked to meet them. The Tsar inquired where the Mennonites were going. “To Molotschna” in Ukraine, they replied, to which the Tsar responded, “I wish you well on your journey. Salute your brethren; I have been there.”

Przechowko Mennonite Church became Alexanderwohl Mennonite Church in Russia, meaning Alexander and “well.” In 1874, because they were losing their religious freedoms in Russia, members from Alexanderwohl Mennonite Church migrated again to Harvey County, Kansas. Elder Jacob Buller led the entire Alexanderwohl Church, plus other families, about 800 persons, as they embarked on two steamships across the Atlantic, sailing to New York City and then by train to Kansas. They built a large meetinghouse in Goessel, Kansas, just a few miles north of Hesston. By 1920, there were almost 1000 members at the church. Today, with approximately 500 members, Alexanderwohl Mennonite Church is a congregation of Mennonite Church USA.

Swiss and South German Mennonites

In 1711, five boats sailed rapidly downstream from Bern, Switzerland, in the mountains, to Amsterdam, near sea level, where the boats stopped. The distance was about 550 miles. Swiss authorities were forcibly removing Mennonites from Bern because of their radical beliefs. The Mennonites believed church and state should remain separate; they called for believers in Jesus to be baptized upon their own decision rather than as an infant, and their commitment to follow Jesus in life meant they would not take up weapons to defend themselves or their government.

The 1711 boats began in Bern, Switzerland, traveling on the Aare River and then the Rhine River, headed north, all the while downstream. They packed what they could in a trunk or two. Officials worked to send all Anabaptists out of Switzerland, with threats of imprisonment or being sent to the Mediterranean Sea to row on ships as enslaved people if they ever returned.

The boat trip lasted twenty-two days, from July 13 to August 3, 1711.8 Four boats were loaded with Amish, and one had Mennonites. Fifty-two were Anabaptist prisoners. About twenty years earlier, a division occurred among the Swiss and South German Mennonites. An Anabaptist minister named Jacob Amman was concerned about the increased acculturation and assimilation of the Mennonites to the ways of the culture surrounding them. Amman wanted to renew the Anabaptist principle of separation from the world and return to stricter congregational discipline. Most Mennonites disagreed with his views, so a division emerged in 1693, with Mennonites following Minister Hans Reist and a minority following Jacob Amman.

The Amish men aboard the boats had long, untrimmed beards, whereas the Mennonite men had trimmed shorter beards. The Amish men wore broad-brimmed felt hats. Dress and hair appearance were not significantly different between the Mennonites and the Amish in the early years of the division. However, Amman’s followers wore plain clothing, and over time, the simple way the Amish dressed became the primary way folks identified them compared to Mennonites.9 The Amish emphasized Christian principles of simplicity, modesty, humility, and self-denial.

On the twenty-two-day boat trip down the Rhine River, most of the Mennonites got off the boats when they stopped at ports along the Rhine, especially Mannheim, but they did not rejoin the boat. Three hundred and forty-six Anabaptists arrived in Amsterdam, most of them Amish. The Swiss exiles lived in large warehouses for two weeks alongside a canal in a busy commercial city, one of the most prosperous in northern Europe. For the plain Swiss farm families recently kicked out of their rural mountain farm homes in the Canton of Bern, Switzerland, Amsterdam seemed strange, cosmopolitan, and worldly.10

During the 1500s and 1600s, the Mennonites from Switzerland experienced persecution in cities, so most moved to rural areas in isolated mountain valleys. Some Swiss farmers had to be careful, or they might fall out of their steep mountain fields. In these rugged mountainsides of refuge, they could live in isolated towns yet still be a witness to their faith in Jesus. Nevertheless, they worshiped together in secret, in caves or hidden rooms in barns. Evangelism was from neighbor to neighbor, and as more and more joined the Anabaptists, it further provoked the authorities who defended the state-controlled Reformed church.

By the early 1700s, it had been five or six generations since the first Anabaptist radicals broke from the Catholic and Reformed churches in Zurich and Bern. Younger generations needed to be taught to accept water baptism when they were old enough to choose it for themselves.

Among the 346 Anabaptist refugees from Switzerland who arrived in the Dutch Republic on August 3, 1711, around a hundred joined the Old Flemish Groningen Mennonites. The Swiss Amish farmers from Bern joined skilled farmers from the Netherlands and formed a new community. Their union reinforced the link between agriculture and simplicity.11 They lived as a close-knit community with farming as their preferred way of life. The Flemish and Swiss farmers found success by shifting from dairy farming to potato production. The Swiss migrants became the conduit for the Columbian Exchange, introducing the potato to the northeast region of the Netherlands.12 Nearby the city of Groningen was the village of Witmarsum, the birthplace of Menno Simons, whose parents were probably dairy farmers.13 Later, in the 1700s, some of those Swiss Amish families in the Groningen region migrated again to Pennsylvania.

The Palatinate and the Alsace were central farming regions for the Swiss and South German Mennonites and Amish. In the French Alsace, King Louis XIV issued royal orders in 1712 to expel about a hundred Mennonite and Amish families. They had improved the land and were successful, but Louis XIV could not tolerate non-Catholics in France.

Mennonite families fled Switzerland and the Alsace and moved north to the Palatinate. Increasingly, because of their farming skills, authorities tolerated Mennonites despite their minority religious status. They farmed on rented land, with leases for varying numbers of years. However, in the early 18th century, their protection fees doubled, and they were restricted in their rights to purchase land. German Elector Charles III limited the number of Mennonite families in the Palatinate to two hundred. Mennonites in the Palatinate met in homes until they built a few church buildings in the late 1700s. Their desire to migrate elsewhere steadily increased.

Mennonite farmers in the Palatinate and Alsace led the agricultural revolution of the 18th century. The three-field system, used for centuries, called for a field to be planted with one set of crops one year, a different set in the second year, and then it was to be left fallow, or with no crops, in the third year. David Mollinger, an outstanding German Mennonite farmer, worked to increase yields from his crops, and he discovered how to replace the traditional three-field system with an intensive use of the land made possible by fertilizers.

When Mollinger purchased a neighboring wooded hill, he planted the bare top in clover and scattered limestone over it, which he ground from his mill, and raised an excellent crop. Instead of letting the land fallow each alternate or third year, as was the practice in Germany, Mollinger discovered he could improve the soil by planting clover for pasture and hay, which put nitrogen in the soil. Farmers began to understand that legumes like clover, alfalfa, and beans took nitrogen from the air and worked it into the soil that corn or wheat could use in the next farming cycle. When Mollinger and other farmers used manure from their cattle as fertilizer, their crops tripled, and the soil’s fertility increased.14 David Mollinger was a key farmer-thinker in the mid-1700s agricultural revolution, which increased the European population as the food supply increased, and stimulated the emergence of a large middle class.15

However, the push to leave Germany in the early and mid-1700s increased for Swiss and South German Mennonites and Amish. After years of leasing land in the Palatinate, old feudal agreements meant that the original Catholic or Protestant owners could take the land away from the Anabaptists at any time. There were also increasing threats to the Mennonite beliefs in nonresistance.

A few Swiss Mennonite and Amish families moved east to Volhynia in Ukraine. They farmed there among Dutch Mennonites and Hutterites until most Swiss Anabaptist families in Volhynia left again in 1874 for Kansas and South Dakota.

Dutch Mennonites were the first Anabaptists to migrate west across the Atlantic Ocean. A few settled in New Amsterdam and lived there when the British took Manhattan Island in 1664 and renamed it New York. At about the same time, Pieter Plockhoy established a small settlement of Dutch Mennonites in Delaware, but it died out by the 1690s. Mennonites arrived in North Carolina in 1710 and the 1750s, but neither settlement lasted very long, and information about those communities and their histories was lost.16

Swiss and South German Mennonites felt pulled to the colony of Pennsylvania. Parents wanted to help their children and grandchildren get started in farming by purchasing more land. The Quaker government in Pennsylvania kept a low profile, essentially absent from the new settlers’ lives.17 William Penn had dedicated his colony of Pennsylvania to be a haven for all kinds of persecuted minorities. Among the 30,000 Germans who migrated to Pennsylvania in the 18th century, about 4000 were Mennonites, and 500 were Amish.18

My Yoder story illustrates the desire and dangers of crossing the Atlantic on a small ship for a new land. The Joders, spelled in Europe with a J, had lived near Bern, Switzerland, for over three hundred years before they fled because of religious persecution. Jost and Anna Joder had their babies properly baptized in the Reformed Church, but all ten joined the Mennonites as adults and were re-baptized.19 They had been invited to join by their neighbors. Jost served on the parish local council, and when he was eighty-five years old, he was put in prison for six months because his children had all left the Reformed Church to join the Anabaptists.

One of Jost and Anna’s sons, Hans, married Catharina Risser, both of them from Steffisburg at the base of the Emmental Alps Mountains. Hans and Catharina joined the Mennonites. One of Hans and Catharina Joder’s sons, Jost Joder Jr., joined the Amish. In 1711, eighteen years after the initial Amish-Mennonite split, Jost Joder Jr., from the Palatinate, was among a group of Amish men who tried one last time to ask for forgiveness and reconciliation with the Mennonites.20 Jost and the Amish men were unsuccessful; the Mennonites did not accept their plea, and the split between Mennonites and Amish became permanent.

Three children of Jost Joder Jr. and his wife Magdalena were aboard the Francis and Elizabeth British ship for probably a month and a half, landing in Philadelphia on September 21, 1742.21 One of the three, Christian Joder, arrived in Pennsylvania with a family of eight children aged 2-17. He was probably an ordained minister, and they settled in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Christian carried a small devotional book with him to the new world, with prayers, hymns, and readings for weddings, communion, and baptisms.22 I am a descendant of Christian and Anna Gerber Joder. A younger brother of Christian Joder, Hans, died during the Atlantic crossing and was buried at sea, leaving his wife, Barbara, a widow in the New World. Christian and Anna Gerber Joder, with their children moved to Berks County, Pennsylvania and farmed. Christian’s last name became “Yoder” in Philadelphia.

Barbara Burkholder, a Swiss Mennonite widow with six children, joined five Mennonite families who decided to migrate to Pennsylvania in 1754. They were part of a Mennonite congregation in the Swiss Jura Mountains. Barbara joined two other widows with children; the three women had 17 children altogether. The records state that the five families were poor, so their Mennonite church gave each family money to travel to Pennsylvania. But the travel loans were to be paid forward to the deacon’s fund in their future Pennsylvania churches.23 Barbara’s son, Peter Burkholder Sr., was 11 when they sailed. It took the families five-and-a-half months of travel by land and ocean to reach Pennsylvania.

Peter Burkholder Sr. refused to muster or march with the Pennsylvania militia during the Revolutionary War and migrated with his family to the Shenandoah Valley in the 1790s. Peter’s wife, Margaret Huber Burkholder, only 48, was buried in Rockingham County, in the Trissels Mennonite Church cemetery in 1798.

Virginia Mennonites ordained Peter Burkholder Jr. as minister (1805) and bishop (1837), and he was the leading minister in a log meetinghouse that folks first called Burkholders and later Weavers Mennonite Church. In 1854, one hundred years after Barbara Burkholder bravely migrated to America, her great-grandson, Virginia Bishop Martin Burkholder, built a red brick house, which the Brethren & Mennonite Heritage Center in Harrisonburg moved onto their campus in 2002.

Renewal and Disruption

With its stunning sketches, Martyrs Mirror circulated widely among Mennonites in the 18th century. First printed in the Dutch language by Thieleman J. van Braght, with excruciating stories of 1,396 Anabaptist martyrs, it was Jan Luyken’s copperplate 4.5 x 5.5 inch etchings that crafted Martyrs Mirror into a living book.

Dirk Willems escaped from prison and crossed a pond with thin ice four and a half centuries ago, but many can tell the story from memory. A guard pursued Dirk, and the guard fell through the ice. Dirk turned around and rescued his captor, who took Dirk back to prison. Later, Dirk was burned at the stake in 1569.24 We know the story because Jan Luyken’s copperplate etching helps us see the story.

In the 1700s, Martyrs Mirror may have been the most important link between Mennonites in the Netherlands, Prussia, the Palatinate, Pennsylvania, Ontario, and Virginia, helping to build a broad Anabaptist identity.25 In 1745, fearing war in the American colonies, Mennonite leaders in Pennsylvania appealed to the Dutch Mennonites for financial help to translate and publish Martyrs Mirror into German for colonial Mennonites, which indeed happened.

Martyrs Mirror reveals that a third of the Anabaptist martyrs were women. The image of Anabaptist Catharina Mulerin, taken to prison in Zurich, Switzerland, shows us the plight of persecuted Anabaptists. Martyrs Mirror images give clarity to faith, inspire thoughts of discipleship and commitment, and encourage perseverance in a hostile world.26 Catharina was released from prison, though she and other Anabaptists in Switzerland were forced to leave their country.

Martyrs Mirror is a big book centered on a minority faith that lives globally.27 Through the centuries, Martyrs Mirror has sustained the Anabaptist community with stories and sketches that describe and show Christian faith in a fallen world.

The Froschauer Bible, printed by Christopher Froschauer in Zurich, Switzerland, was a favorite of Mennonite and Amish immigrants to America. German families brought 170 copies of these large Bibles when they sailed across the Atlantic Ocean.28 Mennonites and Amish liked the Froschauer Bible because its vernacular Swiss-German language was different and easier to understand than Martin Luther’s High German translation of the Bible.

Abraham Strickler (1693-1746) was one of the first Mennonite settlers in Virginia, purchasing land near Luray in 1727.29 Along with farming, Abraham traded with the local Indians for furs and sold them in Pennsylvania.30 Abraham and Anna Strickler brought a large 1536 edition Froschauer Bible to Virginia. His Swiss ancestors hid their family Bible from authorities because it would be taken from them and burned if discovered. The Strickler Bible was a beacon of hope and courage, used at family weddings, marriages, baptisms, and deaths. Abraham’s Bible passed through many generations by marriage for about 450 years. Encased at the Shenandoah Heritage Village Museum in Luray, Virginia, the edges are black from years of use, the cover clasps broken off, and the pages frayed, but the 1536 sketches and German print inside seem vibrant.

The American Revolutionary War, 1775-1781, challenged the nonresistant peace beliefs of the Mennonites in colonial America. The Mennonites tried to remain neutral, but colonial leaders revolted against the King of England. Those who stoked the revolt against Great Britain refused to accept religious beliefs for refusing to fight.

During the Revolutionary War, Mennonites in Pennsylvania were second and third-generation descendants of those who had immigrated earlier in the 1700s. Mennonite church leaders found the spiritual level of their people low during the war, and their beliefs in peace were greatly tested. A few young Mennonite men joined the revolutionary battle against the British, but most did not.

The Revolutionary War was about Enlightenment values of independence, citizenship, and self-rule. Formerly, Mennonites had been subjects of a king, queen, or monarch. They had few or almost no rights. After the American defeat of the British in 1781, Mennonites became citizens of the United States. Citizenship brought responsibilities and challenges that changed the lives of Mennonites and all the American colonists.31

Not long after the Revolutionary War, with confusion over which Caesar to honor—the King of England or the U.S. Congress—about a hundred Mennonites migrated to Canada. In Ontario, they continued to live under the rule of the King of England.

Precontact Indigenous groups, including the Monacan and Manahoac, lived in the Valley of Virginia long before the coming of European settlers. Along the Linville Creek in Rockingham County is an ancient burial ground for approximately eight hundred Native Americans.32 In 1892, the Smithsonian Institution conducted a dig along Linville Creek, but the area is on private land, and few have been able to investigate further. When English surveyors began marking land and claiming territorial rights in Virginia, the native peoples fought back, especially during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), when Indians massacred Mennonite Preacher John Rhodes’ family near Luray, Virginia, in 1764.

After the Revolutionary War ended, Mennonites moved to the Linville Creek region of Rockingham County, Virginia. Those who migrated in the 1780s and 1790s included Brenneman, Brunk, Burkholder, Funk, Geil, Heatwole, Rhodes, Showalter, and Wenger. When the Mennonites cleared land to farm along Linville Creek, the Iroquois and other Indigenous groups had mostly moved away, using the region occasionally to hunt and obtain furs and hides to trade.33

Mennonites followed established patterns of settlement that included the loss of land for Indigenous people groups. Mennonite farmers raised European crops and domesticated animals that included weeds and germs, which remade the natural world and undercut the Indigenous ways of life even in places where direct European-Indian contact was minimal.34

Rockingham County Mennonite settlers also encountered enslaved Africans. In 1788, when Daniel and Margaret Showalter moved with their family to a 158-acre farm they purchased, enslaved Africans had lived in Virginia for 169 years. During the 1700s, three-fourths of all those who landed in British North America were enslaved, indentured servants, or convict labor.35

Summary and Analysis

I’ll conclude with four brief stories and offer analyses.

First story: A hard-working Mennonite farmer in the Palatinate had been accused of becoming wealthy because he made counterfeit money. When his German elector confronted the farmer, the man held out his blistered hands and explained that all his money came from the soil through the hard work of his hands and under the blessing of God.36

Mennonite farming traditions during the 1700s made most of them economically successful. Farming had been their identity, tied in with who they were as a people in community, drawing their sustenance from the earth. It seemed to Mennonites that the earth was alive, feeding them and others while nurturing relationships of mutual dependence.37

The Anabaptist vision in the 1700s remained a lived faith in agricultural communities, though some lived in cities like Amsterdam, Danzig, or Philadelphia. Rural Mennonite churches consisted of families who knew each other in local, face-to-face ways that extended into their day-to-day work. Anabaptist-Mennonite rural communities bore witness to another way of living together in a hostile environment that sustained them and provided food for the broader world.38 Analysis: somehow, someway, keep your hands in the soil.

Second story: Indian warriors and French scouts surrounded the log home of Jacob Hochstetler one night in Berks County, Pa. The French and Indian War was underway, and the Hochstetlers had to decide how to respond. When their dog barked one night in September 1757, Joseph, age 11, and Christian, age 13, reached for their guns to defend the family, but their father, Jacob, told them to put down their guns. Three in the family were killed, three were captured, and their log home burned.39 Most Mennonites in the 1700s held to the way of peace and nonviolence. Analysis: act in ways of peace, teach peace, and promote the peace of Christ in this dark world.

Third story: Elder Gerrit Roosen, from a northern European Mennonite community in Hamburg, Germany, became distressed at the split between the Amish and Mennonites. Roosen disagreed with the strict standards of separation from the world held by the Amish. Mennonite Elder Roosen believed that one should follow the customs of the land and those of the people one lived with.40

In a desire for renewal, some Anabaptist groups reject trends in society and seek separation from the surrounding culture. Other Mennonite groups seek renewal by integrating with the intellectual tools of science and higher education. Analysis: Choose your direction to find renewal; involvement in or separation from, or some degree in the middle.

Fourth story: Maria Bogli, twenty-five and single, accepted the Bern authorities’ offer to sell her possessions and travel on a boat down the Rhine River in 1711. Maria handed over $324, or Thalers, to the government trip manager to be returned to her in the Netherlands. Maria was among 103 Swiss Amish and Mennonite refugees who joined the Old Flemish Mennonite community in Groningen. Maria had been baptized as an infant in the Canton of Bern, Switzerland, and chose baptism again by choice, leading to her removal from the country. Maria began to farm the rich peat soil in the Netherlands. She received $340 from her original $324 two months after she arrived.41 Soon after she settled in Groningen, Maria was able to purchase a house and a plot of land for herself.

At the heart of the Dutch Mennonite interventions with distant governments and financial support for persecuted Mennonites was a growing understanding that the descendants of the 16th-century Anabaptists shared a common identity. They lived as respectful dissenters from the official church and as obedient subjects of the state. In the 1700s, a transnational identity emerged that connected Anabaptist descendants wherever they lived.

A few Swiss Mennonites migrated to Ukraine, a trickle of Dutch Mennonites migrated to colonial America, and German Mennonites crossed an ocean to Pennsylvania. By the end of the 1700s, Mennonites worshiped and farmed along the Dnieper River in South Russia near the Black Sea. Analysis: The growing diversity and transnational Mennonite identity connections increased in the 18th century and again in the 19th century.